Protected by the bones of the skull, your eyes lie inside hollow openings called orbits. Each eye is held in place by six eye muscles and ligaments, and is cushioned by fat. The eye muscles work together so that your eyes move to form a single image. Symptoms of double vision (diplopia) may appear when these muscles are not working together.

Protected by the bones of the skull, your eyes lie inside hollow openings called orbits. Each eye is held in place by six eye muscles and ligaments, and is cushioned by fat. The eye muscles work together so that your eyes move to form a single image. Symptoms of double vision (diplopia) may appear when these muscles are not working together.

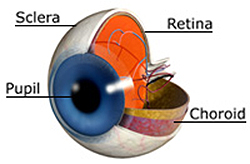

The white outer layer of the eyeball is called the sclera. The conjunctiva is the mucous membrane covering the sclera and lining the eyelids. Inflammation or infection of the conjunctiva or sclera may cause redness, tearing, or discharge of the eye. The clear window covering at the front of the eye is the cornea, which lies in front of the colored part of the eye, the iris.

The inside of the eye is divided into two chambers. The front chamber is filled with a watery liquid called aqueous humor. The larger chamber in back is filled with a soft jelly called vitreous humor. An overproduction of aqueous humor can cause a build-up of intraocular pressure which contributes to glaucoma. Degenerative changes in the vitreous humor can cause symptoms of floaters.

Between the two chambers is a clear disk called the lens. The lens is held in place by rings of muscles that help the eye focus and see at varying distances. Muscles pull on the lens to make it flatter to view distant objects; they relax, allowing it to take a more curved shape for looking at nearby objects. This change in the curvature of the lens is called accommodation. Cataracts result from a natural aging process which causes the clear lens to become cloudy over time and lose its focusing ability. Patients with cataracts may have difficulty seeing at distance, reading newsprint or experience symptoms of glare.

Your eye works somewhat like a camera. Light rays pass through the cornea and enter the eye through the pupil.The pupil can adjust in size to limit the amount of light coming in, much like the diaphragm of a camera. Behind the pupil, the lens bends the light rays. After passing through the fluid in the eyeball, the light rays are focused on the retina.

The retina is a layer of light-sensitive nerve tissue lining the back inside of the eye. Made up of millions of cells, the retina reacts to light. There are two types of cells in the retina—rods and cones. Rods detect the amount of light —from very dim to very bright light. Cones detect the color of the light—red, green, or blue. Those who cannot see a full range of colors are “color-blind”. The center of the retina is the macula which allows us to read and see fine detail. As people age, the retinal cells in the macula can slowly break down leading to macular degeneration. This causes blurry and distorted central vision, but does not lead to complete blindness as the peripheral retina and vision are still intact.

The retina is a layer of light-sensitive nerve tissue lining the back inside of the eye. Made up of millions of cells, the retina reacts to light. There are two types of cells in the retina—rods and cones. Rods detect the amount of light —from very dim to very bright light. Cones detect the color of the light—red, green, or blue. Those who cannot see a full range of colors are “color-blind”. The center of the retina is the macula which allows us to read and see fine detail. As people age, the retinal cells in the macula can slowly break down leading to macular degeneration. This causes blurry and distorted central vision, but does not lead to complete blindness as the peripheral retina and vision are still intact.

The retina reacts when light hits it, sending a message along the optic (eye) nerve to the brain. Because the light rays are bent by the lens, the image formed on the retina is upside down. As the signals are conveyed by the optic nerve, the brain analyzes the information turning the image upright and producing the single image that we see.

Caring for Your Eyes

Even if you are not having difficulty with your vision, periodic eye exams can identify developing problems. The sooner problems are detected, the sooner proper treatment may begin. If you wear glasses or contact lenses, visit the eye physician regularly to monitor your vision and adjust your prescription as needed. If you play sports, wearing safety glasses reduces the risk of an eye injury. People with a family history of eye disease such as glaucoma, macular degeneration or corneal dystrophy should be monitored at regular intervals for the possible development of these conditions. A dilated eye exam allows the physician to monitor the health of not only the eye, but the body as well. Patients with systemic disease such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or heart disease can benefit from annual dilated eye exams.